Tyler Richards was the data analyst for Access Party, and his article “Two Decades of UF Student Government Elections” has remained one of the few publicly accessible data analyses for UF’s student government. The UF_Politics seriousposting team sat down with Richards and interviewed him on Access Party, the #NotMySystem campaign, and data analysis’s importance in student government politics.

Part 1: Access Party

UF_Politics:

What was your involvement in the 2015 formation of Access Party?

Richards:

So I wasn’t actually involved in the formation of Access Party at all when I started. Basically, when Access Party kind of rolled around that first spring of 2015, I had started at UF the fall of 2014, so that was still my freshman year. And so I got involved with everything actually through this group that was called the Freshman Leadership Council.

And they were very System-y, right? It’s one where different houses have a certain number of slots. So like ADPi always has a slot in FLC and Theta Chi always has a slot that they can pick like their freshman to get into it. I don’t exactly know why I got in. I think they probably regretted it because I was very not interested in the System stuff and that’s when I started to understand how politics worked at UF. So then I was like, “Wow, this, this is kind of annoying.” And I had a few friends in FLC that were all like, “Wow, this is really silly.”

Then Access Party came around and we slated and decided to try it out. Then I slated with Access and was there from the beginning, but I wasn’t there before they announced. All of the like knowledge that I have of basically that 30 or 60 day period pre-announcing the slating intention was just from [being] good friends with Elle Beecher [founder of Access]. I know a lot of the Access folks and then later I was involved in leadership within Access, and I learned a lot more of the lore after that.

UF_Politics:

Interesting. So you were very early on in your UF career and you just slated with Access. What was your reaction to Joselin Padron-Rasines’s victory, and why do you think Access won that spring in hindsight?

Richards:

Yeah, I mean, so there’s a bunch of different potential explanations. I think it’s really, really hard for a non-System party to win an executive ticket when they have been around for a while because the message of all indie parties very often comes down to “Let’s change something up, let’s do something different.” And so, in my mind, one of the big reasons why that Access Party had the opportunity to win is that it started in the spring and it was the first semester.

The other part is that there was a real sentiment in 2015 of the communities, mainly BSU, HSA and AASU, that they were underrepresented in student government and basically the way that it usually works, as far as I understand it, cyclically is that the System had gotten powerful enough that they felt they didn’t have to give as much to the communities: they didn’t have to give as many seats in Senate, they didn’t have to give as many Blue Key taps. They didn’t have to give as many favors in order for them to support the System party. And so then the communities got really frustrated. And that is why you saw Joselin and Nick especially, but also Kevin Doan were all really big community members. They were leaders within HSA, BSU and AASU. And it’s not an accident that you had one from each community.

So it’s that combination of, yes you had the community support and then you actually had an indie party that was going to get started that was much more of a traditional indie party where it was like “no System connection, no communities connection.” They were just trying to start their own party. And so there was that party. I forget exactly what they were going to call themselves. But originally it was going to be three parties slating: the “true indie” party, the “communities party,” and then you had Swamp. It was called Swamp back then, I’m pretty sure.

But then the two indie parties came together because the true indie party actually didn’t have enough. They didn’t know who they were going to put up for their president, VP, and treasurer roles and that was already locked down by Access. And so everyone was just like, “Hey, why don’t we slate together and just combine and form one,” which ended up working really, really well.

I think that’s one of the big reasons that Access successfully won. You also had a lot of just really remarkably good talent. Remarkably good talent that was just around and interested in indie movements. I mean, you had Michael Christ and Matt Hoeck who were really good at organizing and figuring things out and were also just good leaders. You had Elle Beecher, who is a really good marketing person. And so the fact that you just randomly had these people that in a very short amount of time would be just outlandishly good at their job — at doing that, doing marketing for free for this small student government campaign was rare, definitely rare in a lot of stars ended up aligning at the same time. And I think if you missed a couple of those big ones, then you’re going to come out a few hundred votes short and end up losing.

UF_Politics:

You mentioned that a lot of the people in Access Party were the members of the communities who were unhappy with the System. Would you characterize Access as more of a coalition of indies and defectors, or would you say it was primarily defectors from the System with some indies sprinkled in? So it was an equal relationship, or was it primarily the System?

Richards:

I would say it very much depends who you ask and it very much depends how System-y you consider the communities. Different communities at different times are more and less System-y. And so that very much changes my answer. But I would say the nicest way to categorize it is a coalition of indies and defectors. Anyone that goes into it and is more on the indie side will basically have the perception that, “Oh, this was just some people that were just leaving the System, but they always wanted to go back.” And a part of that is true. Like there are bloc leaders on the community side that intentionally said, “Hey, we are going to join an indie party so that the System will respect us again and we’ll take our voice more seriously.” And so then, yeah. The answer is it really depends.

I prefer to think about it from the coalition of indies and defectors just from the set of people that I met and was around. I would say a very small percentage of them were just like, “Oh yeah, I’m really just a part of the System. But then, you know, yeah, I don’t actually care about this indie stuff.” So I thought it was — I thought everyone that I met in Access — almost everyone that I met in Access Party was relatively or at least pretty genuine about their desires for being kind of anti-System.

UF_Politics:

Moving on to the later part of Access Party, why do you believe that Access fell apart after spring 2016?

Richards:

I think independent parties that already have a history with the System and the System has a reason to pick off powerful people within the party are more likely to die younger. They’ll be like a brighter flash in the pan. But it is harder to have a sustained movement. With the true indie people, the System is basically never going to go to the true indie people and be like, “Hey, if I give you a Blue Key tap, will you slate in the Senate for me or something?” because all of them would instantly take a screenshot of that and post it on Twitter because they’re more interested in clout and the joke than anything else — than like a Blue Key tap. No one gives a shit about Blue Key.

So because of that, Access Party was uniquely set up where it’s really hard to have a really sustained movement for a party like Access which is a coalition of indies and defectors. I also think that the System did a really good job of recognizing how serious the loss was and changing their strategy or implementing the time-old strategy of “change the name, add more people, and go at it again.” And that strategy very, very often works. And so they executed on that pretty successfully.

Then they were able to woo the communities back really quickly. Before 2015, you basically never saw a member of the communities as the president — as UF president. That was just never an option. It was like, oh, maybe once every two or three years you might get a treasure or a VP slot. And that was how it went. And so then post-Access, I mean, you’ve been around, but post-Access, the world is just entirely different where you cannot have an all-white slate anymore. That’s not something that is manageable for a political party at UF to do because you’ll just lose. And then you very often see members of the communities being put up for the presidency roles.

UF_Politics:

Yeah, I think that is true. I think every Student Body Vice President and Treasurer tends to be from the communities in the System party. It’s very interesting to see that Access was that origin.

Richards:

I mean, the thing is, I would love to see all of that, right? I don’t 100% know that that’s all true. But all I know is from the years 2010 to 2015 or somewhere around there, you very rarely saw two members of the communities as VP and Treasurer, and you never saw a member of the communities as the president.

UF_Politics:

To this idea of defectors, do you know the benefits that were given to people who were former System defectors to go back to Impact after it rebranded? Do you know any details about that?

Richards:

I mean, the easiest example is Kishan Patel. He was a member of Access, and he was a sophomore senator or an engineering senator. I forget exactly what it was, but he was in the Senate and then the — AASU was the current community’s bloc leader at the time. And so then when they made that decision, they were like, “Okay, he’s going to be the treasurer for the next spring as a part of switching over.” And so then he was there and he was the Treasurer that was the easiest example. I remember in the 2016 year basically that the communities got whatever they wanted. Y’know, spring of 2015, 2016 or something, it was just like you could double or triple the number of Blue Key taps in a year that you would normally get. You could do whatever you wanted. And the fraternities, mostly that fraternities, were willing to give up just so much more because they wanted to win.

UF_Politics:

What was the influence of the Bradshaw Papers at the time? They still circulate today in the indie movement, but they were released like 2013ish, and that’s around the time Access started.

Richards:

Yeah, the Bradshaw Papers, they definitely pre-date Access. So it wasn’t like “Bradshaw papers were released, people read them, started Access.” I wouldn’t draw that line at all. So I actually didn’t know that they were published in 2013. But basically in my mind, because I came in fall of 2014, the Bradshaw Papers were something that happened in the past and were not extremely influential on me until…well, I guess they were influential in that they were the first thing that I read that helped me understand everything all at once. And so there were kind of passed around, just kind of passed around.

And so I talked a few times to Bradshaw. And it’s always interesting because, he doesn’t want them published, but he’s fine with other people reading them because when he gave all those interviews, he gave all those interviews under the understanding of a bit of anonymity. And it’s interesting to see how little anonymity there is in them anymore because now everyone knows them — like thousands and thousands of people have read them, probably. And so even though you can’t find them online — you might be able to now, but I haven’t seen them online — but that little fun fact is always interesting to me, that he’s like, “Oh yeah, please don’t share them or post them online anywhere.” Yeah, it’s interesting.

UF_Politics:

Interesting that you actually met Bradshaw in person. I’ve heard —

Richards:

— Oh, no, I didn’t meet him in person. I just met him online.

UF_Politics:

Oh, interesting. Because I’ve heard from people in the movement that Bradshaw really doesn’t like to be contacted about them and that he just tends to brush off a lot of contacts. You have any thoughts on that?

Richards:

Oh, well, yeah, for sure. I mean, so I only met him because someone that was part of one of the indie movements sent him some work that I had done. And then so he had read it and liked it and then we talked. So if you’re just a random person with no new interesting information to give him, just asking him questions about his master’s thesis from ten years ago, he’s going to be like, “Go fuck yourself. I don’t want to talk to you anymore, I’m not going to get anything out of this.” [laughter]

But yeah, I talked to him about the online voting stuff. I don’t think I talked to him at all about like #NotMySystem things, but I shared a bunch of the data analysis and things with him. But lots of people in the indie community are just kind of nerds. I’d say if you’re willing to nerd out with him, then they’ll like you.

Part 2: #NotMySystem

UF_Politics:

Interesting that you mentioned #NotMySystem. So could you explain what #NotMySystem was and what exactly was your involvement in that campaign?

Richards:

Yeah, so the story is that there’s this guy named Manny Rutinel who’s basically the most charismatic person on the face of the earth. And he was a part of Access Party the second year — maybe he was a part of it originally, I forget exactly — but he is super smart, super charismatic. Like as soon as you talk to him, you’d be like, “Am I in love with you? This guy is amazing.” And he was campaigning and talking to people and he was in Turlington or something. And then he ran into this guy named Sabrina. And then Sabrina started just dumping all this stuff on him just like, “Oh, I used to be part of the System. I’m so mad at it, whatever else, yada, yada, yada.”And then Manny was like, “Oh, okay.” And I was friends with Manny. And so then Manny was like, “Hey, can I introduce you to my friend Tyler?” And then she said yes.

And then I started talking with Sabrina. As soon as I met Sabrina, I was like, “Hey, wouldn’t it be fun to make a video about something like this?” And then that night, or maybe a few hours later or something, I contacted Elle Beecher, who I was good friends with at the time — still good friends with. And I was basically like, “Hey” — and the thing Elle is really good at is that she’s very good at taking things and understanding how people will interpret what is being said. And she’s very good at making things popular online.

And just the whole branding side of it was something that she was incredibly good at. So I was like, “Hey, I think it’s something that would be really fun, and I think you’d be a really unique value add to it” because I would think about just doing it alone. And so then, we started talking with Sabrina, and Sabrina was like — I don’t know if you’ve ever talked to her. It’s a little something. She is definitely something.

And I was like, “Alright, well, listen, this is like, this is like a firecracker. I’m holding on to a firecracker right now. I don’t want to hold on to this firecracker for very long at all. I think we should do this in 48 hours or something.” So then over the next 48 hours, maybe it’s a little longer than that, maybe it’s a week, we basically got a video crew that only would do it under the veil of anonymity. And we paid them to create and edit this video that — that was basically me, Elle, our friend Austin Young, who also was not telling anyone that he was a part of this in the slightest because he was a pretty apolitical-type person, or at least in terms of student politics. And then Angel is one of my good buddies from UF, so I brought him because he’s hilarious and really smart.

And so then four or five of us drafted the video, figured out how we wanted to say X, Y and Z, took a few takes in the Reitz. It’s actually filmed in the prayer room in the Reitz. Fun fact, because we didn’t know exactly where we could film it without anyone knowing what we were doing, and no one was using it. And so we were like, “All right, if anyone wants to come in here and pray, we will definitely leave. But we’ll do this here for now.” And no one kicked us out, so we were fine.

And then basically, that was pretty much it. We filmed the video, put it up online, and it went bananas. And by the time that the #NotMySystem thing was going on, I was really sure that we were going to lose. I was like, really sure. I was like, “Oh my God. Like we are going to get creamed in this election.” So it was kind of a Hail Mary type of situation in my mind, where I was like well, let’s see how many people that we can frustrate with this sort of thing. And yeah, and that was the #NotMySystem campaign. Do you have any more specific questions about what went on there?

UF_Politics:

You mentioned the video going sort of super viral. I remember Sabrina was interviewed by the Cosmopolitan and a lot of big outlets, and it got 100,000 views in a few days. But why exactly did the viral success of #NotMySystem not translate into electoral success?

So for context, I think Susan Webster, the Impact President, actually won by the largest number of votes a System candidate has ever gotten in history. I think she got 7.2 thousand votes. And they really swept. And it’s interesting because 2015, the communities split off from the System and there’s, like, a schism and it leads to Access’s victory. While in 2016, Sabrina Philip was this big leader in the System, political bloc. She also splits off, but it doesn’t lead to equal electoral success.

So why exactly do you think #NotMySystem didn’t achieve as much success as it could have or that last year did?

Richards:

So there’s two — in the fundamentals of election science for voting theory, there’s two variables that matter for any individual person. You can basically say me, Tyler, there are variable A and variable B. Variable A is “What is the percent chance that I am going to vote for your candidate?” And then B is “What is the percent chance that I’m going to vote?” And every piece of advertising can either influence A or B.

So if you are a political party or movement, the general idea is that you have to figure out which one of those numbers is more malleable and how to make that number change. And so, for something like a split of the communities, the communities have a set of voters. It’s probably in the single digit thousands, less than that, maybe 1000 or 2000. But let’s say whatever, that they can basically say, “Hey, these people are going to vote almost no matter what, and we can tell them which way to vote. And so we can split the first number but the second number is more static.” For the average student on campus, I think the average student on campus would probably vote for indies. Maybe they’re at like 55%, 60% indies or something like that. But that chance of voting is really, really low. And so that second number, so a lot of indie parties will be like, “All right, my goal is to increase turnout for those people.” And so that is one of the reasons why people really like online voting, because it automatically takes the second number and shoves it up extensively.

Then the the other part — so that that’s the thing about #NotMySystem is that I think didn’t work well is that it didn’t resonate with that fraternity and sorority people at all. Ideally what would happen is basically it would basically the fraternity and sorority people are like, “Oh my God, this is shitty. I’m not going to vote anymore.” But that didn’t happen in the slightest. And as you mentioned, Impact was very easily able to just have a massive, massive turnout. And they were able to do that because of really good execution. And they had been executing extremely well, and they were extremely scared. They were extremely scared by the success of Access.

And so I think basically #NotMySystem had no impact on the number of votes that came out from the System side in the slightest. I don’t think it increased or I don’t know — maybe even they felt more scared and we’re like, “Oh, we got to go crazy because of this whole #NotMySystem thing,” and then more people came out. One of the big ways that the System drums up more support and drums up more votes is basically, they say, “Oh, these people are coming to take away our stuff. We have all this power and this is awesome and so they are going to go and take away these cool things that we have.”

And so the success of #NotMySystem — maybe it didn’t do anything, but maybe it also increased the fear of the System party such that they were like, “Now everyone really has to vote” and they were able to make sure they got all the stickers and all this other stuff. I mean, people go out and vote if they feel like they’re going to get something taken away from them.

And then on the non-System side, I mean I just think people don’t really care about it. They were like, “Oh, that’s crazy.” But it didn’t influence if they were going to go out and vote or not. And I definitely don’t think people didn’t…

The thing is, all of this is conjecture. I would say the number one reason for Access’s 2016 giant loss would have happened regardless of #NotMySystem. I think it wasn’t like, “Oh yeah, we were clearly going to crush it” and win and then got shit on. It’s like no, we were getting dominated the entire campaign. It was not looking good in the slightest. And then at the end of it, let’s throw this little Hail Mary thing. So I’ve kind of been droning on a whole lot, but the number one thing that I think you should take away — that in my mind how people should takeaway is that I think it is pretty unlikely that #NotMySystem is the deciding factor in the spring of 2016. I think it is disappointing that more people didn’t really care about it, but I don’t think it’s that surprising also.

UF_Politics:

Why do you think the average student really didn’t get energized by #NotMySystem?

Richards:

Well, it’s kind of like in national politics, you have all the negative ads where you basically say, “Hey, they’re so shitty. Oh my God, this system is so corrupt or whatever,” and you have all of those types of ads kind of out everywhere. Those ads don’t make you more likely to vote for the candidate that isn’t that shitty side, it just makes you less likely to vote. And so you show — that the reason why negative advertising works is because it shows people that have a reasonably high chance of voting and voting for the other party. It makes that chance of voting go down. It doesn’t change — it doesn’t make them likely to vote for you, it just makes them less likely to vote overall. And that’s why negative advertising works.

And so this is basically a massive negative ad against the System. And so because of that, I don’t think negative ads make the other side more likely to vote.

Part 3: Data Analysis

UF_Politics:

How important is data analysis to both independent and System parties?

Richards:

So I’ll start with the System side. On the System side, the biggest bit of data is turnout data. The things that are closely tracked — and there’s a pretty good operations team for this sort of thing — is “how many people from your fraternity/sorority voted in the last election?” and “what is the percent?” You’ve got 100 people in your house, 200 people in your house. Did you get 90 people to come out? Did you get 150 people to come out? How many stickers do we have? And then that information is tracked closely and people, I mean just get screamed at after night one because it’s tracked after night one. And then they basically say, “Hey, you’re only at fucking 50%, get your shit together. I don’t care after you have to get pledges to go and drag your members out to go and vote. You go and get those people to vote.” So that operation set up is extremely important to the System, and I view that as a form of operational excellence in the System to be able to keep track of that many houses and that many people.

And that is like the fundamental — the thing that the System is really good at, is being able to track votes and then being able to reward and punish people based on that information. So I think that is the data analysis that is really important to System parties. I think they also have a recognition of which seats are important and which seats are not important in the Senate. But that kind of matters usually matters a little bit less just in terms of how many Senate seats exist, because for most of the elections, it’s like, I don’t know — most elections are pretty clear what’s going to happen. There’s only a small number of seats that end up mattering. And so just understanding which seats are likely to win and likely to lose, is like, you don’t have to do a crazy amount of data analysis to know that.

To the independents, it basically started to become a bigger deal with Access, and no one had really done a lot of tracking of data and keeping of data and figuring stuff out in that way until the second year of Access when I was just like, “Oh, this is it was just kind of interesting to me” and so I started messing around with it.

So we started trying a whole bunch of things like trying to see which bus stops were most used on campus based on bus ridership data. And then you’re not allowed to be right next to a bus stop, but you could be kind of closed when people are getting off to see — like that sort of stuff we were trying to figure out.

And then we were trying to figure out how many pledge cards that we had for every seat. And so then we were able to say like, “Hey, we’ve got this number of pledge cards for people that say they’re a sophomore. And we got this number of pledge cards for the engineering seat or for Murphree or whatever.” And then we were able to use those as proxies for how well the candidates are campaigning and if they’re actually doing their part or if they’re slacking off a little bit. And so if someone has like ten pledge cards and they’re running for their freshman seat or something — which is basically always going to go to the System anyway, but still — you can basically take the ratio of the pledge cards and the number of people running for that seat and how many votes that you need to say, “Hey, you should probably double the number of pledge cards that you’re getting.”

We started doing stuff like that. I would say it’s medium important, but it’s probably not — even as a data person — I don’t think it has been a game changer in any election that I was a part of. I don’t think it switched from, “Oh, you’re going to lose. And then you looked at this ratio and did this and then you won.”

UF_Politics:

So can you elaborate on pledge cards? I don’t think that’s common practice.

Richards:

So basically one idea that Access had was that if after you talk to someone, you’d go up and say, “Hey, I’m running for this and this, are you an engineer? Can you pledge your vote to me? Can you give me your number? Can you give me your name? And can you give me your major or something?”

And then on voting day, we basically sit there and have hundreds of these things and then you would text people and just say, “Hey I’m Tyler, I’m running for the engineering seat. Last week we talked and you said that you were going to vote for me. Have you voted yet? Is there any information that you need from me about making this sort of decision?” or just traditional campaigning stuff. And so we use that both for, the main reason why is for turnout and to try and increase turnout on the day of election. And then as a byproduct of that, we were also we tried to create like — I made these big spreadsheets with all of the card information and kept track of made little graphs for who got the most cards and, you know, those sorts of things and try to use that to see which which spaces were doing better or more poorly, better or worse, I guess.

UF_Politics:

Do you think these pledge cards worked to an extent that you would say was satisfactory?

Richards:

Probably. I mean, probably I guess. I think the counterfactual is so hard. And on the day of elections, it’s really hard to know — I mean, it’s impossible to know if someone actually voted. And it’s really hard to know. You basically want to talk to everyone that you’ve already talked to and say, “Hey, here’s a reminder. Please go out and vote for me.” And so I don’t think it’s net negative. How positive it is, I really have no idea.

UF_Politics:

All right. So another question is about specific trends. So your article, “Two Decades of UF Student Government Elections” has remained pretty influential in certain claims it proposes. For example, the article states “an increased number of parties has a significant and negative effect on the number of senate seats an independent party would win.” However, we found anecdotally that to be the opposite.

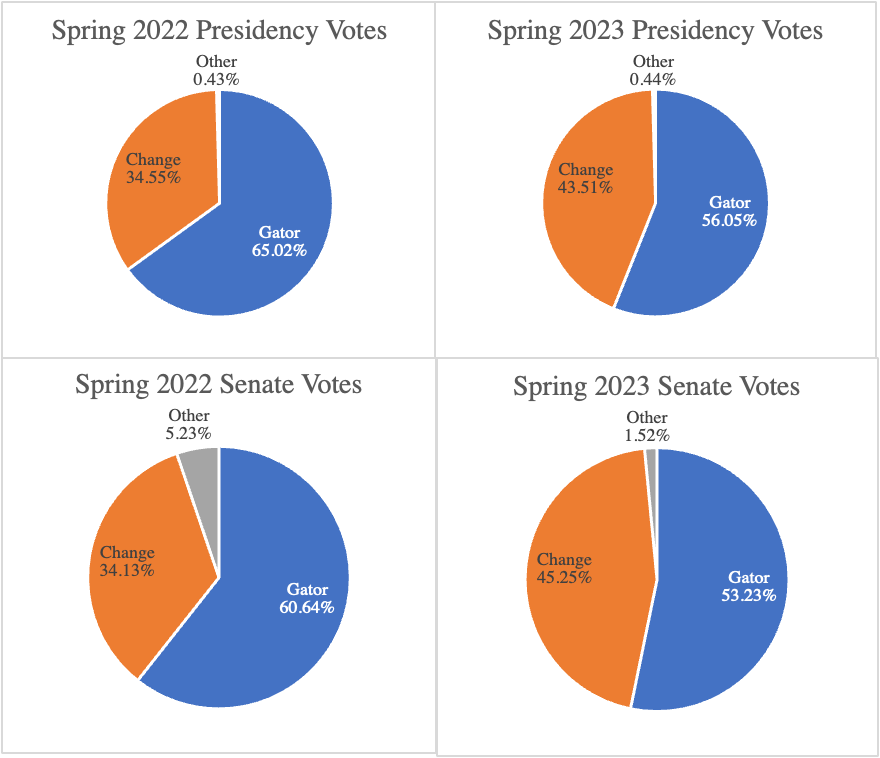

So in the graph below, there’s the Spring 2022 Presidency versus Spring 2022 Senate. And in the Senate, a third party — Communist Party — ran that year, and it seems that they took their 5% of Senate votes, mostly from Gator Party. In certain races last fall [2022], independent candidates in Springs and Yulee also seem to have spoiled votes from Gator, the System party, to secure indie victories.

Do you have any thoughts on this anecdotal evidence? Do you believe that System voters have less voter loyalty than independent voters? Or do you believe this breakdown is lacking in this analysis in any way? Obviously, I’m not a data person. I just made pie charts.

Richards:

I think it’s really interesting. It’s hard to say and I think the way that the reason why it’s tricky in my mind is that the way that you would actually figure this out is through individual seats in the Senate. And if you can say that the ratios were basically…

So I’ve thought about this a bit because you sent me the questions before, and I think it’s a really good point and I think it’s I think it’s extremely hard to know. The way that I would probably do it now is I would say “For elections that had three parties, were there more Senate seats that were won by independents with a three party group, than a two party election?”

And that would be kind of the ultimate way, at least in my mind, the way of doing it because if you just look at Presidency and Senate overall, you don’t exactly know where these are coming from because it’s almost always a question, at least with the Senate of like, “Hey, did they take votes in A or did they take votes in District D” or something like that.

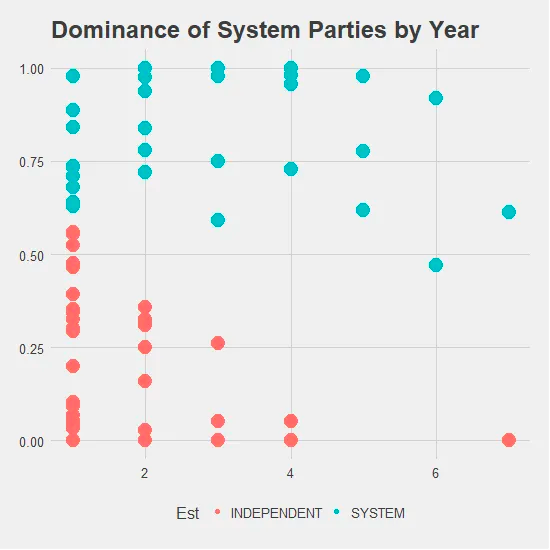

And at least from that, the elections that happened in the small amount of data that I had, which is basically 2000 to maybe like, I think it goes to 1995 or something — whatever it was. 1995 to 2015 or something like that, the number of independent elections were so small that even though I’m technically looking at a pretty large dataset, the number of times that there were three independent parties in a spring election where you could look at this is super small.

And so basically what I’m trying to say is I don’t exactly know. From that dataset, it was pretty clear to me that every time that there were three or more independent parties, which is a really small number of times, the independent parties got fucking crushed. And it wasn’t like, “Oh yeah, like a bunch of frat people decided to vote for some random independent party.”

And it’s kind of interesting because if you just look at Spring 2022, and that’s the most interesting one to me, right where spring of 2022, the presidency has no other votes at all, right. And then Senate has like 5% other votes, which means that someone split. Someone split their ticket and they said, “Okay, on the presidency, that’s the one that the one that really matters, I’m going to vote for the people that I’m supposed to.”

And how I’m interpreting this graph is “The Presidency is one that really matters. I’m going to vote who I’m supposed to. Oh, now, in my little election in District A or something which doesn’t end up really mattering or the freshman seat, which is always going to go for the Gator Party, wouldn’t it be fun to vote for the Communist?” and then you go and you vote for them.

And all the Change people are like, “Oh, I’m going to just vote for Change down ballot.” And that is one way of reading that. The other way of reading that is that there’s this loyalty difference in the indie versus non-indie folks. So I think split ticket, the fact that 5% of people split is nuts. Relative to Presidency versus Senate because you just almost like, I just never — I very rarely see that. I would love to see it broken down by Senate seat and I think you would learn a lot more if you broke it down by Senate seat.

UF_Politics:

Yeah, of course. Thank you so much for your feedback. I definitely appreciate that. We’ll certainly try to do more data analysis on that. I mean, to the extent that we can — with pie charts and graphs.

Richards:

Don’t you have, there’s got to be some data science kids at UF.

UF_Politics:

Change does do their data analysis, but it’s very internal — as in only the top leadership is able to access the —

Richards:

— Only the top, top leadership can access the publicly available [laughter] election results.

UF_Politics:

And so another trend that you outline your article is a decline in indie parties over time. And what’s interesting is the last two iterations of the indie parties — Inspire and Change have defied that trend, often gaining success later in their lifespan. So for example, Change recently won back-to-back Senate victories despite being into its second year. And I think Inspire also won in Fall 2019, which was a good part into its lifespan. I think that was about also two years into its lifespan. So do you have any thoughts on sort of this defiance of the trend by the last two indie parties?

Richards:

Yeah, I don’t see that as a defiance of the trend that much on the second semester.

UF_Politics:

— Er, second year.

Richards:

If it’s the fourth semester that someone is around, then that’s a big difference because when you look at the breakdown of “What is their percent of the Senate that they won?” for a fourth semester independent group, it’s like 10% or something, which basically means they won their five seats that they’re supposed to. Like maybe they won, depending on if it’s fall or spring, they won the graduate seats or maybe they want District D and then lost everything else. But they definitely are not winning District C, which is more of a contentious — yeah, it’s definitely more of a — if you win district C, you probably won like 20 Senate seats or something, at least generally.

So I would say it depends on the year. But yeah, it’s always exciting for me to see independent parties that have a more sustained success rather than what has happened in the data set that I use, which is: they pop up, they do pretty well. There’s literally two examples ever of people winning the Senate or winning a majority in the Senate for an eighth semester. And then seeing people sustain momentum over time is just exciting. That’s the thing that I think is important to understand about data analysis like this is that UF is not embalmed in amber or something. UF is a changing and dynamic place and politics are changing and dynamic.

And just because this is how things have happened in the past is not necessarily indicative that this is how it’s going to happen in the future. And so I hope that for all of these trends, they all turn out to be foolishly wrong in the long term. And I hope that District A all of a sudden becomes extremely contentious and independent parties are able to just do really well in District A and B.

I mean, I ran for District B while I was an undergrad and just got crushed. Crushed, I would go out because it’s just basically like District B’s frat row, so it’s like — what are you going to do? But I hope that all these turn out to be wrong and so I’m excited to see some of them. The more things that I see that are, “Oh, this is not really how this works anymore.” I’m like, “Thank fucking God, that’s awesome,” you know what I mean?

UF_Politics:

And do you have any thoughts — so Access really succeeded because of that schism between the communities and the three blocs. Do you have any thoughts on how — why indies suddenly seem to be succeeding despite a lack of schism? I know you haven’t been at UF for a while, so this might be a bit of an unfair question to ask.

Richards:

No, I mean, the idea is that over the long term, the clout associated with being political in a fraternity and sorority will go down — that is a long term hope. And the hope is that more and more people see it for what it is, which is both stupid and also not useful in your long term career.

And so people had this belief for a while, and this used to be true, where you look at the people that were successful in System parties, and then they go on to do really cool things. And most of the time you see them not anymore. Look at the past five presidents or something and VPs and treasurers and just look at where they’re at now. And then you’re like, “Actually, that’s not that worth it.” You know, lots of them are just kind of fuck ups. And so that’s the hope is that everyone realizes, “Oh wow, this used to be really important and it used to mean something.” And so people were willing to spend and do immoral things to get these positions of power.

And now being UF president means not that much relative to what it did 20 years ago and being in Blue Key. I mean, just imagine — one data point that I always wanted to know is what is the median salary fifteen years later of the engineering graduates that graduated in 1980 and the median salary of Blue Key taps in 1980. So by the time it got to 1995 — and salaries are not a good way of measuring successful careers, I think it’s kind of silly, but there’s some objective number of like, “Hey, if you got to pick, would you rather be a Blue Key tap? Would you rather be an average engineering student?” 1980, I think you pick Blue Key tap because I think there’s a lot of power associated with it and they went on to do interesting, cool things or whatever. Meant a lot.

You do that in 2020, and no way am I taking a Blue Key tap. Now it’s not worth anything anymore. It’s silly. Blue Key is just a silly institution and everyone realizes that. So the hope, at least my hope, is that everyone starts to recognize, “Oh, I thought this was going to be really influential on my career and my life. And now it’s kind of silly and not worth nearly as much anymore. And so I’m not going to do a bunch of immoral stuff to get it.”

UF_Politics:

All right. Thank you for that. And then I have actually another question. How often do indies contact you after you’ve graduated? And what would you say to indies right now who are currently challenging the System?

Richards:

Well, I know I just said that positions of power are silly, and they kind of are. And I’ve changed my mind on these sorts of things all the time. But I would say good luck. It is always fun to be a part of an independent party. I would say that it was really nice in college to have a close group of friends that were doing something that we thought was right and I still think is correct.

And also it was nice to practice losing and know what that feels like publicly because you end up learning a lot personally. And being okay with doing something that you think is right, but you have the recognition that the chance of you really winning in the long term is pretty low, is something that is at the worst case scenario for any parties, a good personal experience. And in the best case scenario, you can make some influential change on campus and actually do good governance, which you have basically haven’t seen from student government, probably, maybe ever. I don’t think there’s been three consecutive years of good governance from UF’s student government, like in the slightest.

I would say people reach out to me every once in a while. I don’t know, probably once every six months, something like that. So yeah, probably once every six months is a rough estimation time, maybe more around election time. I can see how many people read the Medium articles that I’ve written. Maybe 20 or 30 people read it every week, something like that or at least open it. And I have no idea if Medium is inflating those or not, they probably are, but it’s got a good number of reads over the years.

UF_Politics:

That’s very fascinating. And then last question, how has life been after UF and all the student government business?

Richards:

So my life was basically I did data science-related stuff at UF. I was part of the Data Science Informatics Institute thing. That was great. And I did that after I did all that UF election stuff. And then after that I went into election science and I was an election scientist, and did that for a nonprofit.

So the research that I did with Dan Smith and Michael McDonald at UF, so they introduced me to this nonprofit that I was working with my last year at as an undergrad, and they actually read a lot of the UF student government stuff that I had written, and then they were like, “Yeah, I mean, we don’t really need to give you a technical interview because we have all this work is really cool and it clearly shows that you know what you’re doing.” So then I worked for them for a bit out of New York and that was great. I really like them.

Then I went to go and work on integrity-related problems at Meta. So it’s measuring hate speech on Facebook and measuring graphic violence on Instagram, like “how many titty pictures are on Instagram on a given day and how are classifiers to remove nudity” and those sorts of things. And then a lot of that was also kind of election-related as well. They tend to hire lots of election-related folks post-2016. So I did that and that was great. A lot of the lessons that I learned from analyzing this type of data was really useful. At Meta, it was useful for getting me an extremely well-paying job with a nonprofit relative to what I was doing before.

And yeah, so I mean, all that stuff has been really, really helpful for me. And then I haven’t done election science related things in a hot minute because I joined this small startup called Streamlet, and they basically make this open source python library that makes it easy for people to create web apps. And a lot of the reason why I really like the product is because I spend all this time on these data-related projects and then I had to just turn it into a Medium article. And I want people to be able to play around with the data. And so Steamlet makes it really easy to do that. And so I was like, I would have used this like crazy in undergrad and, and at Facebook. And so then I joined them and I’ve been working with them ever since I got acquired by a company called Snowflake for like $800 million last year. So now I work for Snowflake.

UF_Politics:

Thank you so much for the interview. I appreciate you for your time.

Richards:

No problem.